|

|

|

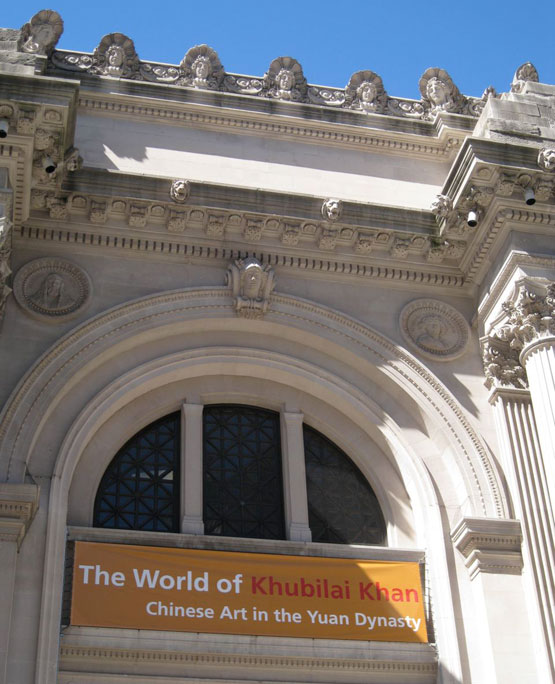

The World of Khubilai Khan:

Chinese Art in the Yuan Dynasty

Metropolitan Museum of Art

September 28, 2010-January 2, 2011

No other museum in the entire world could have done this show!

Curated by James C.W. Watt, Chairman of the Met's Department of Asian Art and one of the foremost Chinese scholars in the world, the exhibition covers the period from 1215, the year of Khubilai's birth, to 1368, the year of the fall of the Yuan dynasty in China founded by Khubilai Khan.

There are over 200 works drawn principally from China, with additional loans from Taiwan, Japan, Russia, Germany, the United Kingdom, and the United States. The assemblage includes every art form, including paintings and sculpture as well as decorative arts in gold and silver, textiles, ceramics, and lacquer.

You will also be able to see new art forms and styles generated in China under the Yuan dynasty and the massive influx from all over the vast Mogul empire.

Curators Maxwell Hearn, Denise Leidy, Jason Sun, John Guy, Joyce Denney, and Nancy Stenhardt assisted Mr. Watt, as did Research Associate

Birgitta Augustin. |

|

Thomas Campbell, Director of the Met welcomes guests to the press preview.

|

|

|

|

You may have heard of Chinggis, or Genghis Khan, whose ruthless conquests spanned the Asian continent in the12th and 13th centuries. His grandson was Khubilai Khan, whose name is also legendary—you may know the rather fantastical poem about him by Samuel Taylor Coleridge. But this exhibition explores the historical reality of Khubilai Khan, who was the first Mongol emperor of China. You see a large-scale reproduction of his portrait on the wall nearby.

The Mongols were nomadic tribesmen from the Asian steppes and redoubtable horsemen and warriors. By the mid-thirteenth century, they had subdued a vast stretch of Asia, reaching from the Black Sea in the West to China in the East. Khubilai Khan ruled over northern China starting in 1260, but a native Chinese dynasty, called the Southern Song, continued to rule in the south until Khubilai conquered it. He and his descendants then ruled a unified China from 1279 to 1368 under the dynasty called the Yuan, which means 'beginning' in Chinese. Under Mongol rule, China witnessed a flowering in all the arts, and this exhibition is filled with treasures from the period. |

|

|

| James Watt, who organized this exhibition. Working with his team of the entire Asian Art Department at the Met, Mr. Watt has spent the last five years basically commuting between Manhattan and the Far East, as well as visiting many other countries that loaned their works. Watt is fluent in both Cantonese and Mandarin. |

|

|

|

| Thomas Campbell, Director of the Met, Emily Rafferty, President of the Board of Trustees, Harold Holzer, Senior Vice President for External Affairs, and Denise Leidy. Ms. Leidy is one of the curators who worked on this show. |

| Entrance to the exhibition. |

Military Official

China

Yuan dynasty (1271–1368)

Marble |

Unidentified Artist

Portraits of Empresses

China

Yuan dynasty (1271–1368)

Album leaf, ink and color on silk

The portrait on the right is that of Chabai, consort to Khubilai Khan. She was a remarkably capable woman who was one of her husband's chief advisers. She was also deeply religious and was said to have persuaded Khubilai to convert to Tibetan Buddhism.

The portrait on the left is that of Targi, wife of the Prince Darmabala (1264-1292), a grandson of Khubilai. She became empress dowager when her son, Qaishan (r. 1308-11), succeeded his uncle as emperor of the Yuan dynasty. |

|

Embroidered Shoe

China

11th–12th century

Wool, hemp, and silk textile upper with silk embroidery, leather sole

Shoe

China

11th–12th century

Wool, hemp, and silk textiles

These shoes, found outside the city wall of Gaochang, are decorated with very small pieces of luxury silks, including both silk gauze and cloth of gold (nasij). The latter confirms the presence of nasij in Central Asia in the eleventh and twelfth centuries and suggests that nasij was used in larger amounts for complete garments. |

Belt Hook

Yuan dynasty (1271-1368)

Jade, with silk band

Excavated from the tomb of Wang Maochang (d.1939).

Zhangxian, Gansu Province, 1972 |

|

Robe with "Braided" (Bian Xian) Waist

China

Yuan dynasty (1271–1368), 13th century

Silk and metallic thread lampas (nasij) with silk and metallic thread samite underflap

This robe--with a flaring skirt, comparatively fitted sleeves, and a wide waistband with simulated braiding--represents the signature garment of Mongol men. This example is an early piece; later examples feature fine pleats beneath the entire waistband, as seen in the wood-block illustration reproduced here. Such garment are described in the Yuanshi as the apparel of ceremonial guards.

The robe must have been dazzling when new. It was woven predominantly with gold thread, its gold now mostly lost. The underflap of the robe is made from a different fabric, with aligned roundels containing addorsed sphinxes, a pattern of the eastern Iranian world. Both textiles are woven in the centuries-old smite technique but, unusual for samite, are patterned with much metallic thread, possibly in response to Mongol taste. |

|

|

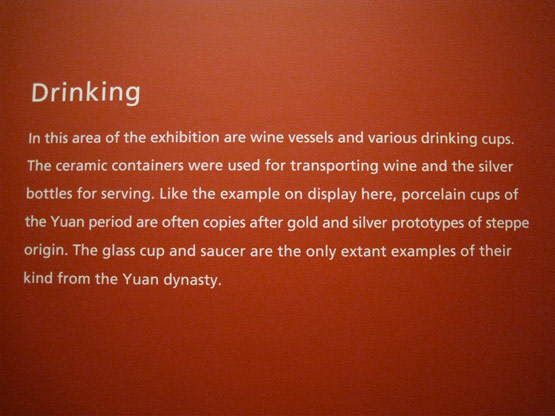

Jar with Lotus Leaf-Shaped Lid

Yuan dynasty (1271-1368)

Porcelain with incised decoration (Longquan ware)

On the sides of this jar are incised the characters qing xiang mei jiu, which translates roughly as "fine wine with delicate bouquet." |

Gold bowl

Xixia dynasty

1038-1127 |

Bottle

Yuan dynasty (1271-1368)

Glazed pottery (Cizhou ware)

Excavated at Jininglu Ancient City, Chayouqian Banner

Wulanchabu, Inner Mongolia, 1958

The characters pu tao jiu ping ("grape wine bottle") are incised onto the shoulder of this bottle. |

Bottle

Yuan dynasty (1271-1368)

Silver

The name of the owner of this bottle is incised on the base in Phagspa, a Mongol script, written with a brush. The character may stand for the surname Yang. It was fashionable in the later Yuan period to mark valuable household belongings with the owner's name in Phagspa. |

Attendants, Guards, and Animals

Yuan dynasty (1271-1368)

Pottery |

Saddle Plates

China

Yuan dynasty (1271–1368)

Gold

These gold sheets, decorated in repoussé, were used to cover a wooden saddle. The patterns are typical of those seen on metal objects on the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries from the steppes of Central and Northern Asia. The motifs of a recumbent deer and lotus plants on the front plate can be seen on textiles and other decorative arts of the same period. |

|

Left: Pass (Pai or Aizi) with Phagspa Inscription

Yuan dynasty (1271-1368)

Silver

Right: Pass (Fu or Pai) with Phagspa Inscription

China

Yuan dynasty (1271–1368), late 13th century

Iron inlaid with silver

Examples of the two most common passes (pai or paizi) used by travelers during the Yuan period. The silver example is of a type that had been used in North China since the Liao dynasty (907-1125), while the round version, of iron with raised silver characters and an animal head in silver damascene, is a Yuan original. Both bear an inscription written in Phasgspa script, so named for the Tibetan monk who devised the script for the Mongol language. The Phagspa script was officially adopted by the empire in 1269.

Roughly translated the inscription reads:

By the strength of Eternal Heaven

Edict of the Khan

He who does not respect

Shall be punished. |

|

| Chris Benfey, who is writing about this exhibit for Slate.com. Mr. Benfey is an Emily Dickinson scholar and teaches a class on the poet at Mount Holyoke College. |

| Andrea Couture, an art critic who writes for the Christian Science Monitor and The College Journal of Religion and the Arts. |

Naomi Takafuchi, Press Associate who has been working at the Met for 17 years. Ms. Takafuchi is standing outside the door to her office. |

Actor in the Secondary Male Role (Fu Mo)

Jin dynasty (1115-1234), late 12th century

Pottery

Excavated from a tomb in Miaopu, Jishan,

Shanai Province, 1978 |

Actor in the leading Male Role (Mo Ni)

Jin dynasty (1115-1234), late 12th century

Pottery

Excavated from a tomb in Miaopu, Jishan,

Shanai Province, 1978 |

Actor in the role of an Official (Zhuang gu)

Jin dynasty (1115-1234), late 12th century

Pottery

Excavated from a tomb in Miaopu, Jishan,

Shanai Province, 1978 |

Actor in the Comic Role (Fu jing)

Jin dynasty (1115-1234), late 12th century

Pottery

Excavated from a tomb in Miaopu, Jishan,

Shanai Province, 1978 |

|

|

Model of a Stage (reproduction) with Five Actors

China

Jin dynasty (1115–1234), dated 1210

Earthenware with pigment

This model of a stage is a vivid reminder of drama under the Yuan dynasty, which is often called the Golden Age of Chinese theater. The elaborate stage building has a projecting roof supported by brackets and an ornamental pediment above. We find these same features in the few stage buildings that survive in China from the thirteenth century. The five figures on the stage represent five types of players in the Yuan theater, each with his or her distinctive costume. You can find the official, with his tall, turban-like headdress. The comic actor is the one who holds two fingers to his mouth to whistle. On the lower part of his robe, he has a funny face, like a mask. It was common even for tragedies to contain some comic relief. The figure in red who twists in a dancing posture is the narrator — in this case, a woman in man's attire. |

|

|

|

Actor Holding a Bottle

China

Yuan dynasty (1271–1368)

Earthenware |

Mongol Dancer

China

Jin (1115–1234) or Yuan dynasty (1271–1368), 13th century

Pottery |

Scene of a Family Watching a Parade

China

Jin dynasty (1115–1234), dated 1334

Stone |

Scene of a Restaurant

China

Jin dynasty (1115–1234), dated 1334

Stone |

Scene of a Restaurant

China

Jin dynasty (1115–1234), dated 1334

Stone |

|

|

|

|

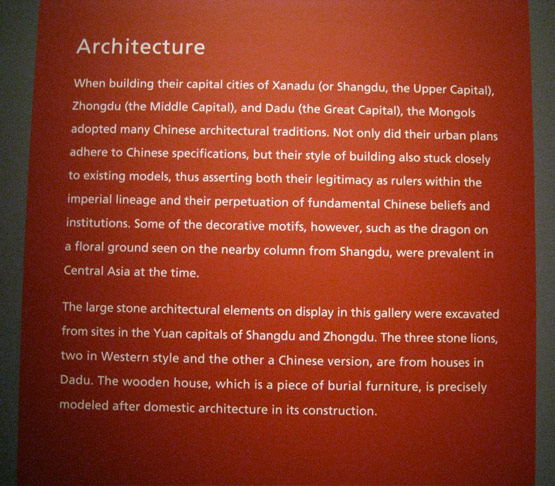

Post with Dragon Design Carved in High Relief

Yuan dynasty (1271-1368)

Stone

Excavated from the site of Yuan Shangdu, Zhenglanqi, Inner Mongolia

This stone post was excavated from the site of Shangdu (Xanadu), the upper Capital of the Yuan dynasty. It once stood at the corner of the front platform of the imperial audience hall. The feisty dragons carved on the stone were symbols of imperial authority and a fittingly grand decorative motif for the architecture it embellished. |

Roof-Ridge Ornament

Yuan dynasty (1271-1368)

Glazed pottery

This large and colorful ornament once adjourned the roof-edge of one of the main halls of Yonglegong, a famous Daoist temple built during the Yuan dynasty. This kind of ornament known as chiwei (owl's tail) or chiven (dragon's snout) first appeared around the sixth century but had by that time developed from a simple carving form into an elaborate embellishment in the shape of a fantastic creature with pointed horns, a wide-open mouth, and sharp fangs. It would become a standard element on religious and official architecture. |

|

|

Jason Sun, a curator at the Met who worked extensively on this exhibit, stands in front of Roof Ornament in the shape of a Dragon.

"This tremendous sculpture once adorned the roof of a large building; it was one of a pair, set at either end of the ridge of a tall gabled roof."

"This one was made of pottery with green glaze so when it was new it was beautiful. Even now it still looks very impressive if you get close. It's a very animated face with a large open jaw and a very large pair of staring eyes. It will give you the sense of the scale of this very large religious building. At the same time, it will show you the splendor of Chinese architecture of the 13th century." |

|

|

Model of a House

Yuan Dynasty (1271-1368)

Wood

This charming model gives us a sense of the way houses were built in China in the thirteenth century. The roof is gabled, with projecting ornaments at the corners. An elaborate system of brackets supports the roof and creates a decorative rhythm beneath it. In the center of the facade is the doorway, with a high threshold and a curving frame. On either side of the door, there are three panels, and in the upper half of each of these is a lattice pattern, which describes the wooden structure set into the windows.

|

Arhat (Luohan)

Northern China

Yuan dynasty (1271–1368), mid–14th century

Wood with traces of pigment |

Bodhisattva Avalokiteshvara

China (probably Hebei province)

Yuan dynasty (1271–1368), dated 1282

Willow with traces of pigment; single woodblock construction |

|

Mandala of Yamantaka–Vajrabhairava

China

Yuan dynasty (1271–1368), ca. 1330–32

Silk tapestry (kesi) |

|

|

|

Central Asian tapestry weaving techniques and Indo-Himalayan imagery are here combined to stunning effect in this spectacular mandala, which was most likely used during an initiation ceremony at court. The donors at the bottom left are identified by inscription as two of Khubilai Khan's great-grandsons: Tugh Temur, who reigned twice as emperor between 1328 and 1332, and his brother Khoshila, who reigned briefly in 1329. Their respective spouses are shown to the far right. This combination of individuals helps date the work to the period between 1330 and 1332.

This tapestry belongs to an Indo-Himalayan tradition of palace-architecture mandalas in which the principal deity, in this case Yamantaka–Vajrabhairava stands in a circle within a square with gateways at the four cardinal directions and further enclosed by three additional rings.

Yamantaka, shown with the head of a bull, conquers Yama, the Lord of Death, and by extension transcends death entirely. Like all terrifying protectors, Yamantaka takes on many manifestations, a reflection of his enormous power. In this manifestation, he also embodies the powers of Vajrabhairava, who has the ability to spur destruction and thereby renewal. |

|

|

|

|

|

Buddha, either Shakyamuni or Akshobhya

Yuan Dynasty (1271-1368), late 13th-14th century

Gilt bronze

Although this Buddha's pointed topknot, triangular face, narrow nose, powerful physique, and scanty clothing are based on Indian artistic traditions, several features suggest that this sculpture was made in China. These include the pudginess of the hands and feet and the patterning in the drapery beneath the crossed legs and on the left shoulder. The lowered right hand reaching toward the earth identifies this sculpture as a representation of either the historical Buddha Shakyamuni or the celestial Buddha Akshobhya, who are the only two Buddhas known to make such a gesture. |

Mahakala of the Tent

Tibet, late 13th-early 14th century

Limestone

It seems likely that small stone sculptures of this sort were produced in Tibet for use there and for distribution throughout China. Mahakala is one of the terrifying protectors of later Buddhism. This manifestation, known as Mahakala of the Tent, was the tutelary deity of Khubilai Khan and of particular importance in China during the Yuan dynasty. In this form, Mahakala has two arms and two legs and holds a skull cap, a knife, and a large staff (his principal attribute). The birds, dog, and wolf surrounding Mahakala are understood as his messengers, and he is flanked by four other figures that serve as his attendants. |

Buddha Amitabha Descending from His Pure Land

China

Southern Song dynasty (1127–1279), late 13th century

Hanging scroll; ink, color and gold on silk

The imagery in this painting shows the Buddha Amitabha descending from his Pure Land to welcome the soul of a recently deceased individual into his paradisiacal abode. Amitabha is one of several Buddhas who create and maintain such realms, and paintings of Amitabha (either alone or attended by bodhisattvas) were among the most widely produced images in China from the twelfth to the fourteenth century. Here, the Buddha stands on two lotuses and holds his right hand in a gesture of welcome. He wears a green undergarment with a wide hem decorated with floral patterns and a red monastic shawl with gold bands. The abstracted folds of drapery on the right arm, the transparency of the green garment as it falls over the arm, and the figure's bean-shaped face are characteristic of the thirteenth century. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Portrait of the Monk Zhongfeng Mingben

Yuan dynasty (1271-1368), 14th century

Hanging scroll; ink and light color on silk

Easily identified by his rounded face and slightly sagging eyes, Zhongfeng Mingben (1263-1323) was one of the most important monks and teachers in China during the fourteenth century. In this portrait , he sits in meditation on an elegant piece of cloth (possibly a carpet) with his shoes placed on a smaller rock in front of him. He wears traditional monastic robes with flowing hems typical of the fourteenth century. The towering pine and delicate bamboo in the background follow the ink-painting conventions associated with the Chinese literati. The landscape is typical of the Yuan dynasty, when such monochromatic backgrounds were first used for the portraits of Buddhist monks. |

|

Architectural Relief depicting the Hindu Legend of Gajaranya Kshetra

China

Yuan dynasty (1271–1368), 13th century

Granite |

Nestorian Headstone with a Cross amid Clouds

China

Yuan dynasty (1271–1368), probably 13th century

Granite |

Pillow in the Form of a Theatre

China

Yuan dynasty (1271–1368)

Porcelain

Hebei Province, where the Cizhou kilns were located, was an area where early Yuan drama flourished. Consequently, ceramic pillows made at Cizhou are often decorated with scenes from popular plays, many with Daoist theme. The scene on the pillow, which has not been conclusively identified, shows two supplicant officials before an emperor in a garden, who is attended by a military officer. The clouds behind the emperor suggest a Daoist association. |

Jar with Eight Daoist Immortals

Yuan dynasty (1271-1368), ca. 1350

Porcelain with mold-impressed relief decoration

(Longquan ware)

The subject of the Eight immortals was a northern Daoist theme that emerged about the beginning of the thirteenth century. It was transmitted south in the fourteenth century together along with the northern predilection for three-dimensional imagery. This jar, produced at the Longquan kilns in southeast China, demonstrates both of these tendencies. |

|

|

|

Boys in a Lotus Pond

Yuan dynasty (1271–1368)

Porcelain (qingbai ware)

|

Tibetan Style Ewer

China

Yuan dynasty (1271–1368), 14th century

Porcelain (Qingbai ware) |

Monk's–Cap Ewer

China

Yuan dynasty (1271–1368)

Porcelain |

Bottle

China

Yuan dynasty (1271–1368)

Porcelain with Splashed Copper Decoration (Jun ware) |

Bottle

China

Yuan dynasty (1271–1368)

Porcelain with underglaze copper red (Jingdezhen ware) |

Yuan dynasty (1271-1368), dated 1295

First section of a handscroll, ink and color on paper

In the early Yuan period, when the ruling Mongols curtailed the employment of Chinese scholar-officials, the theme of the groom and horse--one associated with the legendary figure of Bolie, whose ability to judge horses had become a metaphor for the recruitment of able government officials--became a symbolic plea for the proper use of scholarly talent. Zhao Mengfu painted this work for the high-ranking Surveillance Commissioner Feiqing, who may have been a government recruiter. Executed in early 1296, shortly after Zhao withdrew from civil service, the sensitively rendered groom may be a self-portrait. |

|

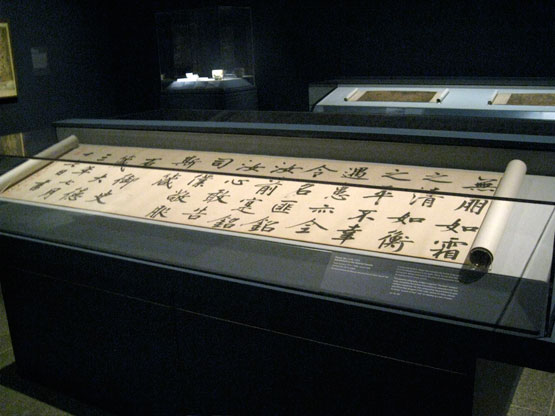

Xianyu Shu (1246-1302)

Admonitions to the Imperial Censors

Yuan dynasty (1271–1368), dated 1299

Handscroll; ink on paper

A northerner by birth, Xianya moved to the former Song capital of Lin'an (Hangzhou) early in his career. There he met Zhao Menufu and became deeply influenced by the ethos of antiquarianism that pervaded southern literati culture.

This powerful calligraphy, written in "fist-sized" standard script, exemplifies the heroism southerners associated with their northern compatriots. The text, composed by the prominent Jin poet and official Zhao Bingwen (1159-1232), exhorts his fellow officials to remain "as pure as frost" and "as impartial as a pair of scales."

|

|

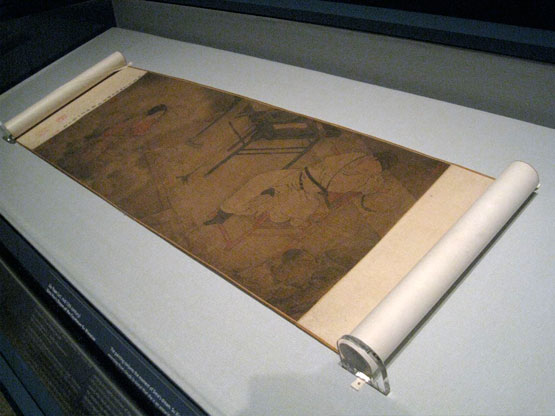

Liu Yuan (act. mid-13th century)

Sima You's Dream of the Courtesan Su Xiaoxiao

Late Jin dynasty or predynastic Mongol period, ca. 1230-50s

Handscroll; ink and color on silk

The painting conjures the moment of Sima's dream. Su Xiaoxiao, emerging from clouds (a signal that she's an apparition), leans toward the sleeping scholar. A number of clues convey the romantic longing and subtle eroticism of the encounter: the romantic longing and subtle eroticism of the encounter: the gentle breeze that tousles Su Xiaoxiao's hair and wafts her scarves toward the young man have also unsettled the candle's flame and pulled at the scholar's cap strings; the patterned silk of her upper garment appears again as the under robe revealed by Sima's provocatively elevated left foot. |

Jar with the Story of Guiguzi

China

Yuan dynasty (1271–1368), 14th century

Porcelain with underglaze cobalt blue decoration (Jingdezhen ware) |

Denise Leidy, who organized the Buddhist part of the exhibition, stands in front of:

Arhat (Luohan)

Northern China

Yuan dynasty (1271–1368), mid–14th century

Wood with traces of pigment |

| Mrs. Richard Oldenburg and Tim Mulligan, Bard Graduate Center's head of Public Affairs. |

Fiction writer Shu Ching Shih. |

Wendy Moonan. Ms. Moonan writes about antiques and is a contributor to NYSD. Behind her in free standing case:

Left: Plate with Qilin Motif

China

Yuan dynasty (1271–1368), 14th century

Porcelain with underglaze cobalt blue (Jingdezhen ware)

Right: Plate with Peonies and Waves in Reverse Pattern

China

Yuan dynasty (1271–1368), 14th century

Porcelain with underglaze cobalt blue decoration (Jingdezhen ware) |

| Edward Maloney viewing Textile with Coiled Dragons. Mr. Maloney was commenting on how strange it still is to turn on the audio guide and not hear Philippe de Montebello after all these years. "But," he added, "Campbell does a great job. They must audition directors by having them do a voice test." |

|

|

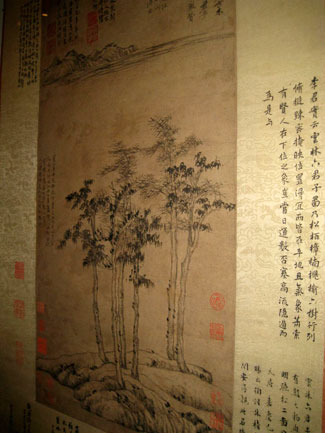

Ni Zan, Chinese, 1306–1374

Six Gentlemen

China

Yuan dynasty (1271–1368), dated 1345

Hanging scroll; ink on paper |

|

Tapestry with Aquatic Birds and Recumbent Animal

Eastern Central Asia or North China, 13th century

Silk Tapestry

The theme of water fowl amid leaves is common in thirteenth century silk tapestries of North and Central Asia. A piece similar to the example seen here was found in the burial pagoda in Beijing of the Buddhist monk Haiyun (1203-1257), an important figure at the court of the early Mongul Empire. The rhythmic background of leaves and flowers also recalls the densely patterned Central Asian silks woven with gold that are preserved in European church treasuries. |

Dish with Design of Two Birds and Hollyhocks

China

Yuan dynasty (1271–1368), mid– to late 14th century

Carved red lacquer |

|

|

|

Plate with Flowering Plum and Birds

Yuan (1271-1368) or Ming (1368-1644) dynasty, 14th century

Black lacquer with mother-of pearl inlay |

Textile with Animals, Birds, and Flowers

Eastern Central Asia

late 12th–14th century

Silk embroidery on plain–weave silk

This textile demonstrates the longevity of motifs in eastern Central Asia. The placement of animas--a spotted horse, a rabbit, and two deer (or antelope)--at its cardinal points is a compositional device that began to appear in the region during the Han dynasty. The birds on the piece, especially the parrot, entered the Central Asian repertoire during a second period of strong Chinese influence, the Tang dynasty. The floral background's central motif of lotus blossoms, a lotus leaf, a trefoil leaf was seen in Central Asia and North China but became widespread during the Yuan dynasty. |

|

Rug with Prunus Branch

This carpet is one of the great peculiarities of the Yuan period, because here you have a clear demonstration of the coming together of two different cultures. In the center of this carpet is the flowering plum, although you can probably see only a few buds, which is one of the most common motifs in Chinese painting and in all the decorative arts.

Surrounding the silhouetted plum branch, on the outer border, there is a pattern meant to imitate Arabic script. This is called pseudo-Kufic decoration, and it's a sign of Muslim contact wherever it appears, from Renaissance Europe to Yuan China.

The carpet is in the collection of the Gion District Association in Kyoto, which holds about five or six examples, and is the only known collection in the world of Yuan carpets like this. It is annually displayed in the Gion festival, which is an ancient Japanese ritual, but it is rarely exhibited in a context like this exhibition. |

|

|

| The Met's Gift Shop, which is very well done. |

| Exhibition catalogue by James C.Y. Watt with essays by Maxwell Hearn, Denise Leidy, Jason Sun, John Guy, Joyce Denney, Brigitta Augustin, and Nancy Steinhardt. Fully illustrated, 360-pages; hardcover $65, paperback $45. |

| Khubilai Khan Red Satin Dragon lined Journal, $14.95. |

| Yuan Dynasty Imperial Passport, $85. |

| Pocket-Size Celadon Ware. Set of 3, $220. |

| Children's books and postcards. |

| Sales associates Yolanda Llanos and Jean Tibbetts in the gift shop. |

|

|

Year of the Tiger Unisex Tee

Adapted from two diverse tiger images in the Museum's collection: the Chinese character for "tiger" in a Northern Song dynasty calligraphy handscroll (ca. 1095) and a proud tiger figure depicted on an earthenware roof tile end (Western Han dynasty, 206 B.C. A.D. 9). $25.

|

|

| Chinese Calligraphy Tote bags, $30. |

| The World of Khubilai Khan. Unframed, $25. |

|

|

| The Met's Board of Trustees hosted a private showing and reception for Supporting Members. |

| James Watt with Mrs. Oscar Tang. |

Graydon Crayton. Mr. Crayton is in charge of the Met's rigging department who put this show together. "Thank God for the equipment. The Official and The Warrior each weigh between 9 and 10 thousand pounds." Mr. Crayton has worked at the museum for 27 years. |

| Derek Weiler and Sabine Rewald, who both work at the Met in the 19th-Century, Modern, and Contemporary Art department. Mr. Weiler is a research associate and Ms. Rewald is a curator. |

Kaska Dratewksa, who is from Poland, is wearing a military look from Michael Kors. |

| Dr. Paul Marks, who used to be the head of Memorial Sloan Kettering. He still works there and is beloved by his colleagues. |

Hwai-Ling Yeh-Lewis, Collections Manager of the Met's Department of Asian Art. |

| Lillie Rodgers and Coralie Bailgey. Ms. Rodgers is a volunteer at the Met in the membership department, and works as an administrator at Touro College. Ms. Bailgey is the supervisor of nursing at Greenwich House, a clinic for Medicare patients. She has been a nurse for the past 50 years. |

| Judith Smith, the Administrator of the Asian Art Department. |

Alexander Clark with his grandmother, Elaine Rosenberg. Mr. Clark is 21 years old and taking a year off from Wesleyan. He's interning at the Met and at Columbia University Press. Mrs. Rosenberg's late husband, Alexander Rosenberg, was a famous art dealer. |

| At a reception in the grand hall, musicians from "Music from China" entertained the Met's guests. |

| Charlotte Soehner practices her Mandarin. Ms. Soehner is the daughter of the Met's librarian, Ken Soehner. She is 10 years old and in the 6th grade at Hunter. |

Music from China is a chamber ensemble that performs a dual repertoire of traditional and contemporary music. |

| Donna Strahan, Conservator at the Met, who worked on this exhibition. "I went over to Beijing to condition report and oversee the packing. When we got back we did another condition report to be sure none of the objects were damaged during the trip." |

Meryl Cohen, the Met's Registrar. |

| Michael Gallagher, Conservator in charge of the Department of Painting Conservation at The Met, with James Watt. |

| Professor Dr. Bernard Maaz had just flown in from Dresden. He is the Director of the Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden Museum. And he had been reading Slaughterhouse Five on the flight to New York. |

Eric Ortel, a banker with J.P. Morgan, and his father, William Ortel, a retired physicist who once worked at Bell Labs and at Verizon. The senior Mr. Ortel 's field was cosmic radiation and high energy nuclear physics. |

| Sinead Kehoe, Assistant Curator of Japanese art at the Met, with James Watt. |

|

|

| A variety of educational programs will accompany the exhibition, including an evening lecture by James Watt scheduled for October 8th, 6 PM in the Bonnie J. Sacerdote Lecture Hall. What a privilege! |

|